In recent years, many companies have come to recognise the advantages of cloud computing. A host of new models have emerged, from infrastructure-, platform-, and software-as-a-service to a wide range of other online offerings. Even tools such as ChatGPT, Google services, and social media platforms are, at their core, cloud services. Used well, the cloud has helped businesses cut costs by paying only for what they actually use.

A large share of these services is either based in the United States or owned by American firms. In recent weeks, several friends and colleagues have asked me how best to manage the risks of hosting software and data in US-controlled cloud environments. Their questions led me to examine the wider transatlantic challenges European companies face.

This report is the result of that work. It does not set out to paint matters in stark black and white. As someone who values open and fair international trade, I want to make it clear that this document is not written in support of, or against, any particular country or provider.

Instead, the report seeks to outline the most pressing risks and challenges likely to affect European businesses. Policymakers and providers on both sides of the Atlantic may yet act before these concerns become unmanageable. Even so, I believe companies cannot afford to be complacent. Resilience depends on preparing for the worst and avoiding over-reliance on any one provider or jurisdiction.

If this report serves as a useful guide for organisations navigating uncertain times, then it has achieved its purpose. A complete list of references is included at the end.

Executive Summary

This report explores the growing legal, political, and strategic risks faced by European businesses, particularly in the UK and Scandinavia, when relying on US cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure. The concerns discussed here are shaped by a combination of legal frameworks and recent political developments, including the EU–US Data Privacy Framework (DPF), US surveillance legislation such as the CLOUD Act, and the January 2025 dismissal of several members from the US Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB).

Key Findings

- The EU–US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) is fragile:

- The DPF facilitates data transfer across the Atlantic, but its effectiveness depends on executive orders and oversight bodies that can shift in response to the political landscape.

- President Trump’s dismissal of PCLOB members in early 2025 severely damaged the scheme’s credibility.

- US and EU laws conflict with each other:

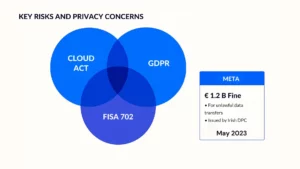

- US laws, such as the CLOUD Act and FISA 702, directly conflict with the GDPR, NIS2, and DORA.

- They allow US authorities to access data held by US firms, even if it’s stored in EU data centres, putting compliance at risk.

- There is an increasingly stronger EU Enforcement:

- The Irish Data Protection Commission fined Meta €1.2 billion for unlawful data transfers, demonstrating that regulators are prepared to enforce the GDPR strictly.

- Legal challenges to the DPF persist and could yet lead to its overturning.

- Europe’s Strategic Response:

- Governments and companies in Europe are investing in sovereign-cloud options.

- More firms are utilising EU-based providers, such as OVHcloud, Hetzner, UpCloud and Elastx, and initiatives like GAIA-X.

- Analyst Advice & Best Practice:

- Analysts (Gartner, Forrester, IDC) recommend hybrid or multi-cloud setups, improving data portability, and using encryption and localisation for sensitive workloads.

- The EU Data Act and CISPE’s Cloud Switching initiative support these strategies.

Recommendations for European Companies

- Carry out Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs)

- Build in contractual and technical safeguards

- Explore EU-based cloud providers

- Adopt multi-cloud architectures and end-to-end encryption

- Conclusion

US cloud services offer many benefits, but their legal and political vulnerabilities may create compliance and operational risks for European organisations. A well-planned, sovereignty-aware cloud strategy is now essential for any business operating in or serving the EU.

Legal and Political Background

EU-US Data Privacy Framework Status

The EU–US Data Privacy Framework (DPF, also known as TADPF) was adopted in July 2023 as a new adequacy decision, replacing the invalidated Privacy Shield. Its purpose is to ensure that personal data transferred from the EU to certified US companies is safeguarded at a level deemed “essentially equivalent” to EU standards.

However, the DPF’s stability is already in question. In January 2025, US President Donald Trump removed all Democratic members of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB), leaving it without a quorum.

The PCLOB is a key oversight body for US intelligence agencies and was integral to the DPF’s privacy safeguards and redress mechanisms. Its hobbling “renders the board impotent as an oversight body and thereby threatens the EU-US Data Privacy Framework”, raising the risk that the EU’s adequacy decision could be rejected by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), as happened to Safe Harbour and Privacy Shield.

Indeed, the DPF’s foundations were already fragile. Trump’s paralysing the PCLOB could contribute to the framework’s collapse when the CJEU reviews it.

EU institutions have taken note: the European Commission’s October 2024 review stressed that it would “closely monitor” PCLOB appointments and reports, and the European Parliament had earlier passed a resolution in May 2023, warning that the DPF “fails to create essential equivalence in the level of protection required by EU law.”

In short, the DPF is in force. Still, its political underpinnings are shakier than ever, given US developments and the ongoing legal challenges. A privacy advocacy group, NOYB, and others filed cases in 2023, alleging that “the fundamental problem with FISA 702 was not addressed,” which could lead to another invalidation.

Limitations vs. EU Regulations

Even if the DPF remains in place, it is narrowly focused on personal data transfer rules and does not override broader EU regulatory requirements.

European laws, such as the GDPR, NIS2, and DORA, impose strict obligations that fall beyond the scope of the DPF. Neither NIS2 nor DORA is covered in the DPF, and additional measures may be required to protect sensitive data in the cloud. The GDPR governs any processing of EU personal data (including security and individuals’ rights), and its cross-border transfer rules (Articles 44–49 GDPR) still apply if the DPF is rejected.

The Network and Information Security Directive 2 (NIS2), which came into effect in October 2024, addresses cybersecurity and operational resilience for essential services, including requirements such as risk management, supply chain security, and breach reporting. Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), effective early 2025 for the financial sector, imposes stringent ICT risk management and oversight of third-party providers, ensuring banks and financial institutions can withstand ICT disruptions.

These sectoral laws require companies to address risks, including data breaches, outages, or supplier failure, as well as legal risks associated with data access, regardless of any existing privacy framework.

For example, DORA and NIS2 effectively compel companies to consider data sovereignty and cloud concentration risks; they “complement and coexist with GDPR,” meaning compliance with the GDPR alone does not satisfy the full spectrum of EU requirements.

In practice, even if a data transfer to a US cloud is legal under the DPF, a European bank or critical infrastructure provider may still face compliance issues under DORA/NIS2 if that transfer creates security or continuity risks (for example, if a sudden legal change renders data inaccessible or compromises it).

Moreover, the DPF is an executive agreement, based on a US Executive Order and an EU Commission decision, rather than a treaty or law; therefore, it is inherently fragile – a change in US administration or policy could unravel without congressional approval.

EU policymakers are well aware of these limits, which is why “in the last decade, there has been a flurry of sovereignty-linked regulation” (GDPR, NIS2, DORA, Data Act, etc.) to shore up protections independently of transatlantic deals.

US Surveillance Laws and Extraterritorial Reach

A core legal concern is that US law can compel access to data held by US-based cloud providers, regardless of the data’s location. The prime example is the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act of 2018, which explicitly authorises US law enforcement to demand data from US tech companies “even if that data is stored outside the US.”

In other words, a company like Microsoft, Amazon, or Google can be served a warrant or subpoena for data in its EU data centres, and US courts assume jurisdiction. This may be directly in conflict with EU data protection laws – as one industry analysis put it, “the GDPR bars transfers of EU citizens’ data to regions with weaker privacy laws, yet the United States’ CLOUD Act compels disclosure of data regardless of its location”.

The question of which law prevails remains unresolved: compliance with a US order could violate the GDPR, risking substantial fines. In contrast, refusal could violate US law. Although, to the author’s knowledge, there is no objective public evidence of US agencies seizing personal data from EU servers (companies tend to resist, and such proceedings are typically secret), the risk is not theoretical.

The infamous Microsoft Ireland case highlighted this conflict from 2016 to 2018: US authorities sought emails stored in Dublin, and Microsoft fought the subpoena. The dispute ended when the CLOUD Act was passed, granting the US government apparent authority.

Under the CLOUD Act, US providers can challenge a data demand if it conflicts with foreign law and involves a non-U.S. person. Still, they must persuade a US judge, and the law grants the government broad leeway.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Section 702, the law enabling NSA mass surveillance of foreign communications, remains in force and was not changed by the DPF. FISA 702 allows US intelligence to collect data on non-Americans outside the US without individualised warrants.

This was a central issue in the Schrems II ruling (CJEU 2020), which rejected the Privacy Shield due to a lack of proportionality and inadequate redress for EU citizens. The new DPF relies on US Executive Order 14086 to impose some safeguards on intelligence agencies. Still, suppose those safeguards are not considered iron-clad (especially with the PCLOB oversight weakened). In that case, the CJEU may again find that the US surveillance laws make EU–US data transfers unlawful.

In short, American cloud giants operate under US laws that Europe cannot ignore: as a tech publication bluntly summarised, “US courts could compel companies under US jurisdiction to disclose data, potentially overriding EU privacy protections in practice”. This extraterritorial reach means that storing data in an EU region of a US cloud alone does not guarantee EU-level privacy or secrecy – a reality now shaping European risk assessments.

Key Risks and Privacy Concerns

Stability and Adequacy of the DPF

European regulators and privacy experts have voiced deep scepticism about the DPF’s durability. EU civil society and the European Parliament were highly critical of the commission’s adequacy decision. The Parliament’s 2023 resolution urged renegotiation of the deal, arguing that it “fails to create essential equivalence” regarding protection.

National privacy regulators, too, have been wary. The European Data Protection Board has acknowledged some improvements (2023). Still, it noted that “some issues of concern previously raised regarding [Privacy Shield] remain valid.”

A fundamental concern is that the DPF, like its predecessors, still relies on US executive assurances rather than statutory change. Max Schrems (whose complaints led to Schrems I & II) has indicated that the DPF will likely be

challenged; indeed, NOYB and others filed suits in late 2023 because US surveillance law (FISA 702) still permits bulk data collection, and the new redress mechanism is not independent.

These cases are expected to reach the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). While a final verdict may be a year or more away, companies risk a “Schrems III” scenario in which the DPF is invalidated, plunging transatlantic data flows back into legal limbo.

The recent turmoil at the PCLOB heightens this risk. Europe saw the PCLOB as a linchpin of oversight under the DPF; with it crippled, the European Commission loses a “key oversight tool for which it bargained”, and the CJEU may view the US commitment as shallow. Since the Trump Administration has fired watchdog officials, privacy advocates claim that the US government undermines the agreed-upon safeguards and fails to implement Executive Order 14086 properly. As a result, the entire framework’s credibility will erode.

In practical terms, this creates business uncertainty: companies relying on the DPF to legitimise EU->US data transfers could suddenly find that mechanism invalid, as happened overnight in 2020 with Privacy Shield. They would then need to scramble to adopt Standard Contractual Clauses or other measures, which face compliance hurdles (regulators, such as the Irish DPC, have already cast doubt upon them, as noted below).

Thus, the DPF’s “long-term sustainability” is a significant concern; many experts view it as a stopgap that may not survive judicial scrutiny, given that the underlying US laws (such as FISA) remain unchanged.

Regulatory and Enforcement Actions

European regulators have not waited for transatlantic politics to resolve. They have begun enforcing GDPR restrictions on cloud transfers in specific cases, demonstrating the real risks of insufficient data protection.

European regulators have not waited for transatlantic politics to resolve. They have begun enforcing GDPR restrictions on cloud transfers in specific cases, demonstrating the real risks of insufficient data protection.

The record €1.2 billion penalty against Meta (Facebook) in May 2023 was a landmark example. Ireland’s Data Protection Commission found Meta’s continued transfers of EU user data to the US (after Privacy Shield’s invalidation, using SCCs) violated GDPR because “the transferred data did not address the risks to the fundamental rights and freedoms of data subjects that were identified by the [CJEU]”.

In other words, Meta failed the “Schrems II” test – the DPC ruled that standard contractual clauses were not enough given US surveillance risks and ordered Facebook to suspend EU→US data flows. This enforcement, the largest GDPR fine to date, underscores that EU regulators are prepared to halt data exports and levy huge penalties if companies can’t guarantee EU-level protection overseas. It foreshadows what could happen to many businesses if the DPF is invalidated or if SCCs are deemed insufficient: any company reliant on US cloud services which handle personal data might face legal orders to localise or delete that data.

European Data Protection Authorities have also cracked down on specific US-based services. For example, several DPAs (in Austria, France, Italy, etc.) ruled that using Google Analytics on EU websites was unlawful because it entails sending personal user info to Google in the US without adequate safeguards. Such cases illustrate a growing compliance risk for EU companies: using popular US cloud services (such as analytics and Saas) can suddenly be declared non-compliant, forcing swift contract changes or technology swaps.

The prevailing concern among regulators is that any data accessible under US law cannot be safely stored in the “cloud” without robust supplementary protections, such as encryption (discussed later). Until US surveillance laws meet EU standards or stronger safeguards are implemented, EU authorities will continue to view reliance on US providers as a legal risk that warrants close monitoring.

Privacy Advocacy and Expert Commentary

Some European privacy advocates have openly questioned whether transatlantic data deals will be upheld. Notably, Marietje Schaake, a former MEP and international policy expert, highlighted a geopolitical dimension: “There is a huge desire in Europe to de-risk or reduce over-reliance on American technology companies because there is a fear that they could be used against European interests”

This statement was issued in March 2025 following the new US administration’s adoption of a tough line on Europe. It isn’t just about privacy laws, it’s about Europe’s digital independence and trust. If EU leaders believe Washington might use its big tech companies to spy or apply economic pressure, they’ll push back.

Privacy advocacy groups, such as NOYB and EDRi, similarly argue that without reform of US spying powers, any “adequacy” is built on sand. They point out that the DPF’s redress mechanism, the newly created Data Protection Review Court in the US, is untested and not truly independent, as the US Attorney General appoints its members; thus, EU individuals still lack an adequate remedy in US courts.

Another often-cited concern is the “persistent problem of FISA 702.” According to privacy groups, as long as bulk data collection is legally permissible in the US, European data will remain at risk.

Consumer organisations in Europe have also chimed in, worrying about cloud concentration. For example, BEUC (European Consumer Organisation) has warned that consumers’ data might be exposed if foreign authorities can access it without a proper judicial process. These voices collectively pressure EU institutions to adopt a firm stance. We have already seen this pressure result in action: the European Parliament’s resolution against the DPF and the EDPB’s tough stances were partly driven by civil society input.

The long-term risk is that transatlantic data-sharing becomes a political football. If the DPF collapses, it could strain economic relations and cause uncertainty for thousands of businesses.

As the Centre for Democracy & Technology noted, the PCLOB firings “severely undermine” the Commission’s ability to ensure the US is living up to its privacy promises, rendering the DPF a futile safeguard.

The EU expert consensus suggests that the current framework may fail unless the US provides stronger legal guarantees. This casts a shadow of risk over any European company that entrusts personal data to US cloud services.

Legal Cases of Data Access

While direct cases of US authorities seizing EU-stored corporate data under the CLOUD Act are not often publicised (due to the secrecy of investigations), the threat is evidenced by preventative guidance from European officials. For example, the Dutch government’s cybersecurity agency (NCSC) issued a memo in 2022 advising European businesses to minimise data exposure to US jurisdiction whenever possible. It warned that “theoretical risks of compelled disclosure to US authorities cannot be ignored”. It outlined scenarios in which EU data could be subject to the CLOUD Act, such as when an EU company is a subsidiary of a US parent or when it utilises a US-based cloud service.

The memo bluntly stated that to avoid the reach of the CLOUD Act altogether, an EU entity must use a non-US provider with no US parent company and ensure the US provider has no “possession, custody, or control” over the EU data.

This kind of official guidance underscores that any data under the orbit of a US company is at risk of disclosure, a view increasingly shared by European regulators. Indeed, Deloitte observes that if a company complies with a US data demand, it may violate the GDPR and face penalties.

A related scenario is government surveillance: Under FISA 702, US intelligence could target a cloud server in Europe if a US provider has access, all without informing the data owner. Although specific instances are classified, the Snowden revelations showed that providers like Google and Microsoft were compelled to give backdoor access to data streams. It is widely believed that cloud providers still receive such orders (e.g., National Security Letters) for data on foreign servers, but they are prohibited from disclosing it.

The absence of transparency (US companies cannot easily reveal how often this happens) further fuels European mistrust. We also observe transatlantic tension in law enforcement access: the US and EU are discussing a potential E-Evidence/CLOUD Act agreement to streamline cross-border data requests; however, until this is implemented, unilateral US orders could conflict with EU law.

In short, this isn’t a distant or hypothetical threat – it’s happening now. European businesses should assume that US authorities can access data held by American cloud providers and plan for it. This risk extends to business continuity: if an EU firm’s critical data were seized or surveilled by a foreign power, that could disrupt operations and breach customer trust.

It also presents litigation risks – individuals or regulators could sue a company for failing to safeguard EU data if such access were to occur. Thus, even in the absence of a headline’ test case” of CLOUD Act vs GDPR, the prevailing risk is the chilling effect and the precautionary principle: many organisations feel they cannot comfortably use US clouds for sensitive data due to the looming possibility of secret access or a sudden legal crackdown.

Transatlantic Business Continuity Risks: All these factors contribute to a broader strategic risk: What if transatlantic data flows are disrupted or heavily restricted? Many European companies, as well as US companies operating in Europe, rely on seamless and secure data exchange with US Cloud services, from CRM and HR platforms to global e-commerce infrastructure, often involving the transfer of personal data back and forth. Suppose the DPF is invalidated, as many anticipate. In that case, those companies might have to suspend certain data transfers immediately or face fines under the GDPR. This is not speculative: recall that Facebook was ordered to suspend EU-to-US transfers and given only 5 months to comply.

If a similar order were to apply to cloud services broadly, companies not prepared with EU-local alternatives could see parts of their IT stack become illegal almost overnight. The risk of a legal “cliff edge” has prompted businesses to push for political solutions. Still, contingency planning is critical given the unpredictable US policy moves (e.g., the PCLOB incident) and court rulings.

Additionally, there’s the risk of a protectionist turn. Data could be weaponised if geopolitical relations worsen (as in the present scenario of rising tariffs and disputes in 2025). The Trump administration’s apparent hostility toward EU privacy concerns (e.g., firing oversight officials and dismissing European criticism) may lead the EU to more aggressively assert digital sovereignty, even if that means temporarily disrupting transatlantic data flows.

For companies, the nightmare scenario is a collapse of data adequacy frameworks without an immediate replacement, forcing them into costly and complex compliance measures for every US data transaction or even requiring data repatriation to the EU. Such instability poses a serious business continuity risk, as it could impact cloud-based supply chains, transatlantic customer data processing, and the viability of US cloud contracts for European clients.

Prudent organisations therefore include these legal and political risks in their overall risk register, rather than viewing them merely as abstract legal matters.

Strategic Responses by European Companies and Governments

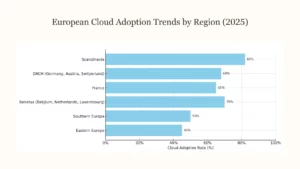

Due to these risks, European businesses, particularly those in the Nordics and those operating in highly regulated fields, have begun to adjust their cloud strategies. There has been a clear trend lately to reduce dependency on US “hyperscalers” (e.g. AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud) in favour of European-based cloud solutions or a more diversified approach. In early 2025, Wired reported “early signs that some European companies and governments are moving away from using American cloud services…citing privacy concerns and uncertainty over US policy.” dev.ua.

Two European cloud providers – Exoscale (Switzerland) and Elastx (Sweden) – noted a surge of inquiries from organisations looking to “abandon US cloud providers” in the weeks following the new US administration’s actions.

The CEOs of those companies confirmed that demand from across Europe has spiked. “Especially customers from Denmark… have been very clear that they want to move away from American companies because of the US administration,” said Exoscale’s CEO, referring to heightened Danish concerns in light of Trump’s rhetoric about Greenland.

Elastx’s CEO echoed that sentiment, calling it a big concern that “from a European perspective, the US is maybe not on the same team with us anymore.

This drives organisations to seek European alternatives. These anecdotes illustrate a larger pattern: clients, particularly in Northern Europe, actively request cloud options that ensure data remains under EU jurisdiction.

Company Examples – Moving to European Clouds

We see concrete examples of companies executing cloud reversals, also known as “repatriation” of data. The founder of a small Austrian tech firm, SkunkWerks, shared that since the start of 2025, he has migrated several servers and databases from American providers to European services, motivated by principle (“privacy is a right, not a privilege”) and pragmatism (avoiding support for policies he disagrees with).

A German healthcare software provider, Medicusdata, which serves hospitals in Europe, stated that while it has always kept patient data in Europe for compliance purposes, clients have recently begun demanding data residency. The company now relies solely on European cloud providers and has migrated its services to a provider based in Switzerland.

This trend is noticeable in the UK and Scandinavia. According to an Investment Monitor report, “a growing number of companies are switching away from American cloud providers, as worries about data sovereignty become more pertinent for their customers and themselves.” This includes UK businesses despite the UK not being in the EU; the geopolitical climate, as well as the UK’s data adequacy deals, also make them cautious.

The UK’s financial services and public sectors have recently been exploring European cloud options to ensure compliance with the UK GDPR and preparedness for potential divergences with US policy.

Public Sector and Government Initiatives

In 2025, the Dutch parliament made a decision supported across party lines to reduce dependency on US tech companies and switch to European cloud providers. Around the same time, over 100 European organisations signed an open letter calling on the EU to become “more technologically independent,” warning that the status quo, dominated by foreign technology, poses “risks to security and reliability.”

Such pressure drives European administrations to invest in local or sovereign cloud solutions. France and Germany have been leaders in this arena: France launched a “Cloud de Confiance” (Trusted Cloud) initiative requiring that cloud services for the public sector should be operated by companies under French/EU law (This has lead to partnerships like “Bleu” – a joint venture with Microsoft Azure technology but under French control). Unfortunately, this project has been delayed and has been effectively put on hold or redefined since 2023–2024.

Germany’s telecom giant T-Systems has partnered with Google Cloud to offer a “German sovereign cloud,” where T-Systems manages the keys and access, insulating the service from US intervention. However, this is not entirely true; the solution is not completely isolated from Google’s American system. In Sweden and Norway, public agencies have closely followed guidance from their data protection authorities to avoid using US cloud services for any sensitive personal data. For example, Sweden’s education authorities warned schools in 2022–23 against using American-based cloud tools, such as certain Google services, after rulings that they could violate the GDPR. These moves have only intensified with the new uncertainties: “digital sovereignty” is now a strategic objective in many national digitalisation plans.

European Cloud Providers and Solutions

The changing landscape has expanded the number of European cloud providers, including OVHcloud, Scaleway, Hetzner, UpCloud, City Network, Elastx, and Exoscale. Although collectively, they still hold a minority share of the European cloud market, they leverage sovereignty as a selling point. OVHcloud (France) and Deutsche Telekom’s infrastructure arm have marketed themselves as GDPR-compliant by design, immune to extraterritorial laws.

For example, OVHcloud and other EU providers joined CISPE (Cloud Infrastructure Providers in Europe) to emphasise data protection commitments and lobby for fair competition with the US giants. According to Wired, companies like Exoscale and Elastx have seen clients “starting to do so” – i.e. actively switching over in the first quarter of 2025.

Some high-profile cases: The French Ministry of Health’s Health Data Hub moved off Microsoft Azure to a European-hosted solution after pressure from the CNIL (the French Data Protection Authority), which was concerned about US access. The German state of Hesse migrated its school systems from Microsoft Office 365 to a local cloud service for similar reasons.

In Denmark, certain municipalities and even private companies have begun mandating EU-only cloud options in RFPs (requests for proposals) for new IT projects. This trend is also driven by increasing cloud service prices and lock-in. Scandinavian companies, in particular, have been early adopters of privacy-focused cloud services – for example, Finland’s UpCloud and Sweden’s Elastx report that fintech and healthcare startups, which handle a lot of personal data, prefer them over AWS and Azure to avoid legal complexity.

“Sovereign Cloud” Offerings by US Providers

Interestingly, the US hyperscalers have responded to European strategic demands by launching Europe-specific cloud environments. Amazon Web Services announced a “European Sovereign Cloud” initiative in late 2024, starting with a dedicated region in Germany that is physically and operationally separate, run by AWS’s European personnel, and keeps all data and metadata within EU borders.

Microsoft has rolled out its EU Data Boundary for Azure, Office 365, and Dynamics, aiming to ensure that by 2025, all customer data of EU clients remains within an EU or EFTA data centre. Microsoft and Google are also partnering with European firms. Google collaborates with T-Systems in Germany to offer a “Germany Sovereign Cloud,” where data residency is guaranteed in-country, and the local partner holds encryption keys rather than Google.

Even Oracle has launched an EU Sovereign Cloud region, and IBM offers EU-only cloud zones. These moves are acknowledgements by US providers that they must alleviate European fears by localising data storage and limiting administrative access. However, European regulators and experts note that these setups have limitations. Because the parent companies remain under US jurisdiction, there is concern that even a so-called sovereign EU cloud operated by a US firm might not resist a CLOUD Act demand.

AWS, Microsoft, and Google argue that using EU legal entities and strictly EU-based staff for these special clouds can create a buffer against US orders. Yet, as Blocks & Files noted, they “are subject to US jurisdiction under the CLOUD Act, potentially compromising [GAIA-X’s] goals” of data sovereignty.

Indeed, one French cloud provider, Scaleway (and later Hosteur), quit the GAIA-X initiative in 2021 to protest US big tech involvement, doubting that true sovereignty could be achieved with them at the table.

Still, for European companies that cannot entirely drop US platforms, using these “EU sovereign” offerings mitigates risk, and likely reduces casual data transfers. It also enforces stricter EU law processes, even if they may not withstand an extreme legal conflict.

Multi-Cloud and Hybrid Strategies

A practical new strategy is to adopt a multi-cloud or hybrid cloud architecture. Instead of putting all their eggs in one provider’s basket (especially if that provider is foreign), companies often spread their workloads across different clouds, using US providers, European providers, and, in some cases, private or on-premises clouds for their most sensitive data.

This approach offers flexibility and leverage: if legal conditions change or a provider becomes problematic, workloads can be shifted to the other cloud environments. For example, banks in Scandinavia use hybrid cloud setups,

keeping customer account databases on a private or EU-based cloud while using US cloud services for less sensitive analytics or web content, and linking them through secure APIS.

Some organisations have negotiated contractual exit or contingency provisions in their cloud contracts. The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) recommends that companies include “springing SCCs”, essentially backup standard contractual clauses that automatically kick in if the DPF adequacy is invalidated.

This contingency planning is part of a broader playbook: companies should prioritise their data transfers and have fallback measures (such as quickly transferring data to an EU cloud or invoking pre-signed data processing addenda).

This contingency planning is part of a broader playbook: companies should prioritise their data transfers and have fallback measures (such as quickly transferring data to an EU cloud or invoking pre-signed data processing addenda).

Many firms in Europe are indeed rehearsing these scenarios. For example, a large Nordic insurance company might maintain a global presence on AWS. Still, in parallel, it keeps an updated clone of critical data in a European cloud environment. If transatlantic transfers are halted, services can be seamlessly cut over to the European zone with minimal downtime.

This is essentially building resilience against legal shock. Surveys indicate that multi-cloud adoption is now standard – over 90% of businesses globally use two or more public cloud providers, and Europe is no exception. European companies give themselves options and bargaining power by avoiding lock-in to a single US vendor. It also helps address another risk: vendor lock-in and dependency can be costly, aside from jurisdiction issues, so multi-cloud strategies support sovereignty and operational resilience.

European Cloud Alliances – GAIA-X and Beyond

On a collaborative level, Europe launched GAIA-X in 2019 as a flagship project to foster a federated, interoperable data infrastructure across European providers. GAIA-X’s goal is to make it easier for European businesses to use home-grown cloud services that meet common standards for security and transparency. It’s not a cloud itself but a framework and ecosystem. In theory, GAIA-X could enable a company to seamlessly integrate services from multiple European clouds, thereby reducing the appeal of the integrated US hyperscalers.

Progress has been slower than hoped, and as noted, the involvement of US firms in GAIA-X raised questions. Still, GAIA-X symbolises Europe’s intent to achieve cloud sovereignty, ensuring that “European data remains under European control.”

EU countries have also formed the European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge, and Cloud, pooling investments to develop next-gen cloud capacities under EU rule. At the national level, initiatives such as France’s “SecNumCloud” label, a cybersecurity certification for cloud providers that, at the highest level, requires immunity from non-EU jurisdictions, and Germany’s secure cloud projects are creating trusted zones for sensitive data.

The EU is also advancing frameworks, such as EUCS (EU Cloud Security Certification Scheme), to certify cloud services at different security levels. Initially, drafts included strict sovereignty requirements, including EU ownership and control at the highest level. However, this has been hotly debated and amended. The mere discussion of such requirements has likely nudged some companies to consider EU-owned providers to “future-proof” their compliance.

Lastly, some European firms are doubling up on-premises or private clouds for specific data. While “cloud-first” remains the mantra for innovation, we now hear “cloud-smart” strategies, such as a Swedish manufacturing company deciding that its crown jewels (sensitive R&D data) will stay in a self-managed data centre or a Europe-only private cloud. At the same time, other workloads go to a public cloud.

This way, if legal conditions worsen, the most critical data is not at risk of foreign access. So, if the legal climate shifts, your most vital information stays out of reach. E.g. sorting and segmenting data based on how sensitive it is; only personal customer details and trade secrets remain on EU soil under EU control.

In short, organisations and governments across Europe, particularly in the UK and the Nordics, are taking both practical and policy measures to address the risks of relying on US cloud services. Their responses include migrating to European providers, reducing vendor lock-in, adopting hybrid and multi-cloud strategies, and strengthening legal safeguards (e.g., SCCs in place as a backup). Using US cloud services must be done carefully to stay compliant and keep things running smoothly, even in a worst-case scenario.

Industry and Analyst Perspectives on Mitigation Strategies

The present development has attracted significant attention from various sources. Analyst firms such as Gartner, Forrester, and IDC have been tracking the rise of cloud sovereignty as a major trend in Europe.

According to Deloitte’s 2024 predictions, “the national focus on cloud sovereignty will intensify in all developed markets”, and specifically, government spending on sovereign cloud solutions was forecast to grow sharply (they

projected government-targeted cloud services to reach $41 billion in 2024, up 16%.

Market data support this: IDC predicts global spending on sovereign cloud services will soar to $258 billion by 2027 (from approximately $80 billion in 2022), indicating an explosive demand for solutions that maintain data under specific jurisdictional controls.

The European market primarily drives such growth. Forrester Research’s forecasts for 2025 explicitly state that Europe will “invest in Sovereign Cloud”, anticipating a boom in European cloud initiatives and a shift in enterprise behaviour (Forrester analysts noted that Europeans are feeling “grouchy” about the economic outlook and tech dependence, which translates into increased support for local cloud alternatives).

In practical terms, major consulting firms advise clients to adopt multi-cloud and hybrid cloud solutions for improved performance, cost efficiency, and risk mitigation in the event of sovereignty issues. A 2023 McKinsey report found that more than one in three European companies intended to have more than 50% of their workloads in the public cloud by 2025. Still, those plans were contingent upon resolving security and regulatory concerns.

In 2025, with concerns still present, the trend is toward balanced cloud strategies: companies want public cloud innovation without single-vendor lock-in or legal vulnerability.

Vendor Lock-In and Portability

Analysts frequently emphasise data portability as a critical capability in the present environment. Suppose an organisation can easily move its data and applications from one cloud to another. In that case, it can swiftly respond to regulatory changes or vendor issues. Recognising this, the EU’s new Data Act (entered into force January 2024) contains provisions to “prevent vendor lock-in” in cloud services. It will require cloud providers in the EU to remove unjustified technical or contract barriers to switching and even mandates the phasing out of switching fees by 2026–2027.

Industry groups, such as CISPE (Cloud Infrastructure Providers in Europe), have proactively developed a “Cloud Switching Framework” with technical specifications to facilitate multi-cloud adoption and ensure interoperability, thereby complying with the requirements of the Data Act.

Interestingly, AWS is a member of CISPE and has endorsed this framework, indicating that even the largest providers see the writing on the wall, customers will demand the freedom to move data.

Analysts view this as a positive development: easier switching reduces the risk that a customer is stuck with a provider that becomes legally problematic. Hybrid cloud solutions, such as VMware-based stacks that can run on-premises or across multiple clouds, are also touted as a way to maintain flexibility. Gartner has pointed out that having a cloud-agnostic architecture can allow an organisation to shift workloads in response to compliance needs. However, it may come at the cost of foregoing some proprietary services of each cloud.

Consultant Guidance on Compliance

Consulting and legal advisory firms in Europe actively guide clients on compliance in the face of these uncertainties. Common recommendations include performing detailed Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs) for any cloud service involving personal data, essentially analysing what laws apply (e.g., the US CLOUD Act) and ensuring that measures are in place to mitigate them. Furthermore, they often recommend adopting encryption and pseudonymization as key technical measures to ensure that the data remains unintelligible even if it is transferred or accessed.

For example, Deloitte notes that some companies use end-to-end encryption, where only the customer holds the keys: “While service providers might hand over data to law enforcement, the data would be unintelligible without the decryption keys.”.

This aligns with European Data Protection Board guidance, which has recommended strong encryption as a supplementary safeguard when using cloud services under SCCs (post-Schrems II guidance). Another piece of advice is data localisation for specific categories of data – essentially, data sovereignty by design.

Gartner recommends a data strategy that utilises global clouds for public, non-personal, or low-sensitivity data, while retaining regulated or high-risk data on sovereign clouds or private infrastructure. This approach lets businesses benefit from cloud scalability for everyday operations, while protecting the data that matters most to regulators.

Innovation and Sovereignty

Analysts warn against completely decoupling from US tech, which could hamper innovation. The consensus view is that there must be a balance.

A Forrester analysis in late 2024 stated that organisations can achieve digital sovereignty targets using foreign cloud vendors alongside native options. Companies might mix and match or use foreign providers on their terms, with contractual and technical controls.

They cite examples, such as European public sectors adopting Microsoft Azure via a locally operated cloud, as in Germany, as a pragmatic compromise. Major consulting firms, such as Accenture and Capgemini, have begun offering services to establish “trusted cloud” environments for clients – essentially layering additional encryption, key management, and audit controls on top of hyperscale platforms to meet EU compliance requirements. This indicates a market solution path: compliance wrappers over global clouds.

In the view of many industry observers, the genie is out of the bottle regarding cloud – companies won’t return to purely on-premises solutions across the board. However, the way forward in Europe is a more federated cloud ecosystem, with a focus on compliance.

Multi-cloud and edge computing can balance workloads across different providers instead of depending on a single foreign provider. Data portability rights and standards, driven by the EU Data Act, will facilitate easier switching between providers if needed.

According to analysts, the likely future is Hybrid Sovereign Clouds – a mix where critical data and workloads run on sovereign-compliant infrastructure. In contrast, less critical functions run on global clouds, managed in a unified framework. This approach, along with regulatory guardrails, should mitigate the most significant risks of lock-in and compliance violations.

Economic and Market Forecasts

Analysts note that Amazon, Microsoft, and Google continue to dominate the European cloud market, collectively holding an estimated 70% market share.

European providers are growing, but from a small base. If the requirements for sovereignty tighten, market shares may shift, giving regional providers a stronger competitive edge. Analysts from Synergy Research and IDC have noted that some large European enterprises now have the bargaining power to demand special terms from US providers. For example, large banks might require that their data never leave Europe and that providers notify them of any government access requests.

If such demands become standard, US providers must offer more customised “sovereign” services, potentially raising costs. Gartner’s recent IT spending forecast indicates that European IT spending on cloud services is expected to continue rising, with an estimated 8.7% growth in 2025. Still, the allocation of this money is shifting – more towards private or sovereign solutions, and perhaps slightly less towards generic public cloud solutions.

These observations suggest European organisations actively manage cloud risk through strategy and technology, driven by analysts’ frameworks and predictions.

Most forward-looking guidance emphasises the importance of resilience, flexibility, and compliance. A 2025 Forrester report on cloud trends predicted that European firms would back sovereign cloud initiatives, prepare for tighter regulations, and work to prevent service disruptions.

The main takeaway is that the industry is aligning to support a multi-cloud, sovereignty-aware paradigm in Europe, where companies can continue innovating with cloud computing without being overly exposed to risks associated with foreign jurisdictions.

Recommendations

Given the current landscape, European companies (and multinational companies operating in Europe) should adopt a multi-pronged approach to ensure compliance and reduce dependency risks associated with US cloud providers. Below are key recommendations combining legal, technical, and strategic measures:

Given the current landscape, European companies (and multinational companies operating in Europe) should adopt a multi-pronged approach to ensure compliance and reduce dependency risks associated with US cloud providers. Below are key recommendations combining legal, technical, and strategic measures:

Comprehensive Risk Assessments

Start with a complete data audit and risk assessment of your cloud usage. Map out the types of data you store or process with US-based cloud providers (including EU data centres operated by US companies) and classify them by sensitivity, for example, personal data or critical business information. For each category, conduct a Transfer Impact Assessment to evaluate how U.S. laws, such as the CLOUD Act or FISA, could affect that data.

Review whether your current transfer mechanism (DPF, SCCs, etc.) is sustainable or if gaps exist. This assessment will help identify the most sensitive data and set clear priorities for risk mitigation. Keep track of legal developments, for example, if the DPF were to be invalidated, all transfers under it would immediately require an alternative legal basis. Preparing documentation such as TIAs and contractual clauses in advance can save valuable time in the event of regulatory changes.

Strengthen Contractual and Policy Safeguards

Use contractual measures to your advantage. If you are using US cloud providers, insist on clauses that demand that data will be stored and processed in Europe, granting you the right to be notified of any third-country data access requests (to the extent permitted). Implement “springing” Standard Contractual Clauses in agreements – meaning the SCCs are pre-signed and will automatically govern transfers should the adequacy framework (DPF) be nullified.

Ensure your contracts allow you to suspend transfers or terminate the agreement if laws change or the provider can no longer meet EU requirements. Under DORA (for financial entities), you will be required to have exit strategies for critical ICT providers – start drafting those plans now, detailing how quickly and by what process you could switch providers or bring services in-house if needed. For intra-group data flows (e.g., between EU and US corporate affiliates), consider adopting Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) if feasible, as they are specifically designed for multinational companies and carry a significant level of commitment (although they, too, rely on the assumption of adequate protection).

Additionally, internal policies should be updated to classify what data can be stored in which clouds (for example, a policy might specify that customer personal data from the EU can only be stored in EU-based data centres and not in any US region). These policies create organisational awareness and can be shown to regulators as evidence of compliance diligence.

Implementing Technical Safeguards

As a key layer of protection, use strong encryption and robust access control measures for all cloud-stored data. End-to-end or “zero knowledge” encryption ensures that the cloud provider does not have access to the decryption keys. So even if they are compelled to hand over data, it remains gibberish. For example, client-side encryption can be used for cloud storage (tools that encrypt data before sending it to the cloud) and to manage the keys on EU soil (or with a trusted EU third party).

One strategy is to use an external key management service or a hardware security module (HSM) based in Europe, separate from the cloud provider. Some providers now offer “Bring Your Own Key” or “Hold Your Own Key” options. Deloitte emphasises that if data is handed over under the CLOUD Act, encrypting it so that only your company (in the EU) has access to the key will mitigate GDPR exposure.

Additionally, pseudonymization (replacing personal identifiers with codes) should be considered before sending data to the cloud. This means that the data does not include personal information unless combined with the information you store locally. In sensitive sectors, emerging technologies such as confidential computing keep data encrypted even during processing. Some cloud providers offer this feature, which can reduce the risk of data leakage or exposure. Essentially, the goal is to enforce technological sovereignty and ensure that the data stored in a US-controlled cloud is unusable to anyone except you and authorised EU-based parties.

Adopt a Multi-Cloud/Hybrid Cloud Architecture

Avoid over-dependence on any single external provider. Design your IT architecture to be cloud-agnostic and portable, allowing integration between various cloud platforms. If you use containerisation (e.g., Kubernetes) or virtualisation that can be deployed across different clouds, it would be much easier to move from one cloud to another. Multi-cloud doesn’t necessarily mean higher cost or complexity if managed effectively – many tools are available for multi-cloud management.

Distributing workloads allows you to localise critical data on a trusted (EU) platform and use other clouds for less sensitive tasks. For example, keep your primary customer database on a European or private cloud and use a US cloud to serve global web content or run large-scale compute jobs on anonymised data. Ensure that your backup and replication strategies are up to date by maintaining cloud data backups in an alternative location, preferably under EU control.

This protects against outages and allows you to migrate quickly if legal issues necessitate a change. Embrace the hybrid cloud by integrating on-premises systems with the cloud. Some enterprises bring specific workloads back on-prem (repatriation) to regain control. If you can’t go fully multi-cloud due to application constraints, negotiate flexibility provisions with your provider and start pilot projects with alternative providers to build familiarity. The

new EU Data Act will make switching easier by forbidding egregious penalties for porting data; take advantage of this by planning a cloud exit strategy for each major cloud service. Test your ability to export and import data elsewhere regularly. Such drills should be part of your disaster recovery plan.

Engage with Stakeholders and Keep Ahead of Regulatory Changes

Companies should stay closely informed on relevant legal and political developments, given the fluid situation. Assigning internal or external legal counsel to track this (e.g., following updates from the European Commission, EDPB guidance, court cases, and US legal changes, such as a possible renewal or amendment of FISA 702) is essential. Be prepared to adapt compliance measures when the CJEU issues a ruling or the US enacts a new privacy law.

If the DPF gets thrown out, regulators might give you extra time or explicit instructions to help you adjust. Stay informed about updates from the European Data Protection Board and your national data protection authority, enabling you to act promptly. At the same time, many European businesses, through their trade groups, call for reliable data-transfer rules. Taking part in public consultations or submitting your feedback can help shape practical solutions.

For example, the Cloud Code of Conduct by CISPE or other co-regulatory efforts often welcomes corporate input. In case the US and the EU consider a CLOUD Act executive agreement or enhanced redress. In that case, companies can support advocacy that pushes for stronger protections, eventually easing the regulatory burden.

Until then, keep legal documentation handy, updated privacy notices, informed consent where applicable (though consent is hard to use for large-scale transfers, in some niche cases, it might apply), and clear records of where data goes. Being transparent with business partners and customers about your cloud sovereignty posture can also build trust. For example, some firms now include in their privacy communications that “we store EU personal data in Europe with XYZ provider and have measures against foreign access.” This kind of openness will be expected by European clients moving forward.

Leverage European Initiatives and Trusted Services

You may want to consider using or switching to EU-based cloud providers or “sovereign cloud” offerings for at least part of your cloud needs, especially for highly regulated data. The European cloud market has matured – providers such as OVHcloud, Hetzner, Scaleway, UpCloud, and City Network offer competitive services and often explicitly guarantee that all data remains in Europe, in compliance with EU law.

Many are also part of GAIA-X, meaning they adhere to standards of interoperability and transparency. If absolute data sovereignty is required (e.g., defence or government data), consider specialised solutions such as on-premises cloud appliances from prominent vendors (some providers can deliver a scaled-down cloud stack that runs in your data centre under your complete control) or community clouds operated by consortia of European firms.

Take advantage of EU governance frameworks where possible. Joining GAIA-X can help future-proof your architecture by making it easier to move between providers. Once in place, the EU Cloud Security Certification (EUCS) will allow you to choose certified “high assurance” cloud services. You may also want to require that critical systems adopt these certified options as soon as they become available through procurement.f

Furthermore, sector-specific communities (like the European Banking Cloud Forum, if one exists, or healthcare data hubs) can share sovereign cloud resources or best practices. Some companies are also looking into decentralised cloud solutions (for example, Cubbit, mentioned in some reports, offers decentralised storage that divides data across nodes, adding resilience and sovereignty by design). While such technologies are still new and merging, they demonstrate innovative approaches to ensure that no single foreign cloud provider holds all your data.

Ensure Compliance with EU Regulations (GDPR, NIS2, DORA)

Cloud risk management should be integrated with broader compliance requirements. Under the GDPR, robust records of processing are maintained, including the location where data is stored and the countries to which it is transferred. Be prepared to demonstrate to a DPA that you have evaluated the risks of using a US provider and implemented safeguards (these are tied back to TIAs).

For NIS2, which many medium/large companies and providers fall under, ensure your cybersecurity measures cover cloud environments. Cloud configurations should be audited to ensure they comply with NIS2 security requirements. Create an incident response plan that covers cloud-specific breaches, and make sure you understand the timelines for incident reporting.

For financial entities under DORA, engage with your critical cloud service providers to ensure they comply with the forthcoming oversight. DORA will empower regulators to audit critical ICT providers, likely including major cloud providers that service financial organisations.

Diversification of providers is implicitly encouraged by DORA to avoid single points of failure; regulators will expect to see that you can switch or have backups if one provider fails. By meeting these EU regulations in letter and spirit, you inherently mitigate some US cloud risks – for example, NIS2’s focus on supply chain security means you will scrutinise the cloud provider’s subcontractors and policies, possibly opting for those with stronger data localisation.

Plan for the worst case

Develop a contingency plan for a scenario where transatlantic data transfers become untenable (e.g., DPF is rejected, and SCCs face heavy doubt or regulatory suspension). This plan should include how your business would continue operating. Identify which processes would be impacted (for example, if you use a US-based CRM for all customer data, how quickly could you pivot to an EU-based instance or an on-premise solution?).

You may consider maintaining a backup system hosted in Europe that can take over immediately. Another concern is that the US administration may initiate retaliatory acts or change rules without notice. If transatlantic data flows are disrupted, the American-hosted services you rely on could also be affected, so ensure you have contingency plans in place.

Ensure that key personnel, including those from the legal, IT, and operations teams, are aware of this plan. Essentially, this scenario should be treated like a disaster recovery situation, as losing the ability to transfer data is equivalent to a system outage for data-driven businesses. Some companies may even simulate “Schrems III fallout” as an internal exercise to test readiness.

Engage Cloud Providers on the Issue

Don’t overlook the fact that, as the customer, you have influence. Communicate your requirements and concerns to your cloud providers. The more customers demand sovereignty features, the more providers will develop them. If you are a significant client, ask your US cloud provider for assurances or solutions – for example, can they commit contractually to challenge any government request for your data and, if legally possible, redirect it to you? Some providers might be willing to specify in the contract that they will use the CLOUD Act’s provisions to fight on your behalf (if the criteria are met).

While they can’t guarantee the outcome, it adds a layer of commitment. Also, inquire about their roadmap for EU sovereign offerings (many have announced plans, but check timelines and scope). Participate in user groups or advisory boards that these big providers have for European customers; those forums are an opportunity to keep pressure on for privacy-respectful features. In parallel, follow the initiatives of cloud provider alliances (such as CISPE) – support their codes of conduct, which often include adherence to EU laws and transparency obligations.

Holistic Strategy

A sound approach is to think holistically: combine legal safeguards such as contracts and compliance with technical measures like encryption and multi-cloud setups, and add a measure of common sense by choosing reliable EU providers and keeping your options open. This amounts to “digital sovereignty by design” – building control into every step of your cloud journey. Done correctly, it ensures that you remain in control of your data, regardless of the vendor or location. In this way, European firms can continue to benefit from cloud services while mitigating the legal and practical risks associated with US providers.

Compliance should not be viewed as a one-time exercise, but rather as a continuous responsibility. Please set up a team or task force to monitor your cloud use against changing laws and adjust your strategy as new guidance appears, such as when the European Data Protection Board updates its GDPR advice. With steady oversight, cloud sovereignty can become a strength, demonstrating to both customers and regulators that your data is safe, compliant, and firmly under your control, regardless of the circumstances.

Conclusion

The rules surrounding transatlantic data transfers and cloud computing are becoming increasingly complex. With the EU–US Data Privacy Framework under scrutiny and US surveillance laws largely unchanged, the legal basis for relying on US cloud services remains uncertain. Recent political developments, such as the dismissal of members of the PCLOB, have further weakened confidence in US commitments to privacy.

European companies, therefore, face difficult choices: whether to continue using US providers despite the risks, invest in European alternatives, or build hybrid strategies to balance compliance with business needs.

European firms, particularly those in sensitive or highly regulated sectors, should adopt a proactive approach to safeguarding legal compliance and ensuring operational continuity. This may also ensure that they can maintain customer trust. The growth of European cloud providers, together with regulatory backing for data portability and sovereignty, is creating a realistic alternative for the future.

Businesses can manage risks without slowing innovation by using hybrid or multi-cloud strategies, implementing robust safeguards such as encryption, and aligning with existing or emerging European standards. The strategic shift toward digital autonomy in Europe is a legal necessity and a competitive opportunity for companies that embrace it early.

The article was updated on 11 December 2025 with information that there are no clearly defined Microsoft services in Europe, but that these projects have not been completed or have been significantly delayed.

If you would like to discuss your cloud strategy, cloud migration, software development, cloud solutions, system integration, or any other topic, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Historical review of important events.

The table below outlines key developments, examples of on some responses, and the legal risks for European firms that rely on US cloud providers:

| Development / Example | Details and Implications | What it means |

| EU‑US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) adopted (Jul 2023) | A transatlantic data deal allowed certified US companies to receive EU data. It provided the legal basis for many EU→US transfers. However, it relies on US executive orders and oversight bodies, elements now under strain. | Temporary relief is available for companies, but the framework is fragile and faces potential legal challenges, including those related to Schrems III. |

| PCLOB Members Dismissed (Jan 2025) | President Trump fired PCLOB’s Democratic members, crippling the board iapp.org. PCLOB played a key role in DPF oversight, specifically through annual reviews of US surveillance safeguards. | The oversight gap undermines DPF and raises the risk that the CJEU will invalidate the adequacy finding. The EU Commission is monitoring; companies face uncertainty as the future of DPF darkens. |

| European Parliament Resolution (May 2023) | The EU Parliament voted that the DPF “fails to create essential equivalence” and urged improvements. Though non‑binding, it reflected broad EU scepticism. | Political pressure on the Commission suggests that if DPF terms are not met in practice, EU institutions may seek to suspend or renegotiate them. Companies were warned that DPF was not universally endorsed in the EU. |

| Legal Challenges to DPF (late 2023) | NOYB and others filed cases at the CJEU, arguing that DPF is invalid due to unchanged US laws (especially FISA 702). The case is pending. | The court will likely review the DPF within 1-2 years. If successful, DPF could be rejected, forcing companies back to SCCs or other tools, or requiring data localisation, high legal risk for any company depending solely on DPF for compliance. |

| Meta fined €1.2 billion for EU‑US transfers (May 2023) | Irish DPC fined Facebook for violating GDPR via data transfers on SCCs. Meta ordered to suspend EU→US data flow. | Landmark enforcement shows regulators will penalise companies if US law access risks aren’t mitigated. It highlights that SCCs without robust supplementary measures are high risk. All companies were effectively put on notice to re‑evaluate cross‑border data safeguards. |

| CLOUD Act & US Surveillance Conflict | The US CLOUD Act allows authorities to compel US cloud providers to hand over data stored in the EU. FISA 702 enables US intelligence access to foreign data without a warrant. | Fundamental legal conflict: Compliance with US orders can breach GDPR. EU businesses risk GDPR fines if such access occurs. This underpins regulatory warnings and drives the need for encryption and sovereign‑cloud measures. |

| Dutch Government Motions (Mar 2025) | The Dutch Parliament passed motions to reduce government reliance on American cloud service providers. | Government IT projects in the Netherlands are expected to shift toward EU providers. This could signal to the private sector that even governments distrust foreign clouds for sensitive data. It could inspire similar actions in other EU states, making sovereignty a policy priority. |

| Open Letter by EU Orgs (Mar 2025) | Over 100 organisations urged Europe to become “more technologically independent”, citing security and reliability risks in the current status quo. | The growing industry and civil society push for EU cloud sovereignty. Reinforces the trend of investing in European cloud alternatives (GAIA‑X, etc.). Companies may feel reputational pressure to act in line with these values (e.g., choosing a “trusted cloud” could become a selling point). |

| Companies Migrating to EU Cloud Providers (2024–25) | Ex: Swiss cloud Exoscale and Swedish Elastx report a surge of EU customers moving off AWS and Azure in early 2025. Danish clients explicitly cited US political concerns; Austrian firm SkunkWerks moved servers to EU cloud dev.ua; Medicusdata (EU health IT) shifted workloads to EU cloud at client demand. | Real‑world shift to European clouds to mitigate legal risk and reassure customers. These example migrations indicate that viable alternatives exist and are competitive. However, transitioning can require significant effort in re‑platforming and retraining IT staff. |

| UK Companies’ Stance (2025) | Under the uncertain transatlantic climate, UK businesses are also switching away from American providers, despite the UK having its own data transfer “bridge” with the US. | UK firms fear similar sovereignty issues, as US surveillance concerns could affect the UK-US data deal. They join their EU peers in adopting multi-cloud or EU-cloud solutions. The UK’s stance matters because many of its operations are intertwined with the EU’s; a divergence could complicate compliance if the UK adopts a more lenient approach. However, the current trend indicates that the UK is leaning towards a more cautious approach. |

| GAIA‑X and European Cloud Initiatives (2019–…) | GAIA‑X launched to build a federated European cloud ecosystem. Dozens of EU providers are involved, aiming for common standards, interoperability, and keeping data under EU control. Some US firms joined, raising concerns, for example, Scaleway’s 2021 exit due to fears of the CLOUD Act. | If GAIA-X succeeds in the long term, European companies will have a richer choice of interconnected local clouds, reducing their reliance on US giants. GAIA-X membership can serve as a quality marker in the short term, indicating that providers adhere to EU values and standards. Companies should monitor GAIA‑X offerings as they are presented, which could ease multi‑cloud management and ensure compliance by design. |

| “Sovereign Cloud” Offerings by US providers (2022–25) | Leading cloud providers have implemented various mitigation solutions. For example, AWS launched the EU Sovereign Cloud in Germany, an EU-only service that ensures that staff and data remain within the EU. Microsoft is implementing an EU Data Boundary for all services. Google partnered with T-Systems for the German sovereign cloud. Oracle opened EU sovereign cloud regions. | These are attempts to comply with EU requirements and retain EU clients. They can reduce data transfer latency and establish operational control in Europe. Still, they may not entirely prevent US legal reach. Companies using these services should still exercise caution (e.g., encryption) because US parent companies may ultimately be required to intervene. Nonetheless, they represent improved options for compliance, likely to satisfy many EU regulators for non-highly sensitive data. |

| EU Data Act – Cloud Portability (Jan 2024) | The EU’s Data Act was enacted, and cloud switching and portability rules were applicable by September 2025. The act requires the removal of unfair switching fees and technical obstacles, while also promoting the use of standard formats. | Vendor lock-in is expected to diminish over the next few years, allowing companies to adopt multi-cloud strategies. As a result, dependence on any US cloud can be reduced with less friction. Companies should plan to utilise these rights – e.g., negotiate shorter contract terms or test migration processes, knowing that switching will get easier and cheaper legally. |

| DORA and NIS2 in effect (2024–25) | The Digital Operational Resilience Act (for the financial sector) and NIS2 (for essential services) impose strict ICT risk management requirements, including oversight of third-party providers and developing continuity plans. | Companies in scope must ensure their cloud providers (which are often US firms) are thoroughly assessed, and backup arrangements exist. Regulatory scrutiny of outsourcing concentration risk is increasing – regulators may question a heavy reliance on a non-EU cloud for critical operations. This pushes the adoption of multi‑cloud or EU cloud as part of compliance. Even companies not directly subject to these laws feel the indirect effect, as best practices trickle down. |

| Potential CJEU Ruling (“Schrems III”) (2025/26?) | Expected Court of Justice decision on DPF’s legality in the next 1–2 years. Suppose the court invalidates the DPF (as many anticipate, given current issues). In that case, companies will return to SCCs plus supplementary measures or halt transfers. | High risk of legal upheaval – akin to July 2020 Schrems II. Companies must be ready (SCCs in the drawer, alternative processing locations). |

| US–EU Political Climate (2025) | There is increasing tension (e.g., hypothetical tariffs on US services, the US President’s hostile stance on EU digital policies). Tech CEOs are aligning with the US administration, and the EU is discussing strategic autonomy. | Geopolitical risk: Data flows could turn into bargaining chips. If trust breaks down, the EU may respond with restrictions or other measures. This makes the challenge not only a legal one but also a strategic issue for companies. Just as diversifying energy supply provides a buffer against geopolitical shocks, diversifying the cloud supply chain can reduce risk and build resilience. |

Sources

- AWS European Sovereign Cloud, Announcing the AWS European Sovereign Cloud. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Azure, Dataethics Largest Danish Municipality Choses French Cloud Provider over Microsoft. 23 Apr 2025. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Betley, Bernardo et al. 2 Apr 2024, McKinsey, The state of Cloud Computing in Europe Increasing adoption low returns huge potential. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Bolans et al., Simon. Stephenson Harwood – The EU Data Act: Switching, interoperability and prevention of unauthorised access to non-personal data. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Brnakova, Jana, 25 Aug 2023, Revolgy – The top 10 public cloud providers 2023. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Burgess, Matt. Wired (2025) – Trump’s Aggression Sours Europe on US Cloud Giants. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Court of Justice of the European Union, 6 Oct 2015, Press Release Safe Harbour invalid. Verified 27 April 2025.

- CapGemini, Cloud Transformation in the Financial Sector. Verified 27 April 2025.

- CIO Dive, Cloud Switching Europe. Verified 27 April 2025.

- CISPE, 1 Aug 2024, Cloud Switching Framework. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Chan, Kelvin & The Associated Press. Fortune, Microsoft says it will ‘vigorously’ contest any government orders to halt cloud operations in Europe: ‘If we ever find ourselves losing, we will put in place business continuity arrangements’. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Cleura 27 Mar 2024, How vendor Lock-In Bleeds Public Resources, Sparking Danish Investigation into Promoting Open Source Alternatives. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Cubbit – Decentralised Cloud Storage in Europe. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Court of Justice of the European Union, Schrems II Ruling. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Dillet, Romain, Tech Crunch. 12 Oct 2020. France’s Health Data Hub to move to European cloud infrastructure to avoid EU-US data transfers. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Dan Milmo & Lisa O’Carroll, 22 May 2023 The Guardian. Facebook fined for mishandling user information in Ireland . Verified 27 April 2025.

- Damon Garn, Tech Target. 17 Jul 2024. The pros and cons of sovereign clouds. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Deloitte, 2025 Tech Trends. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Deslorieux, Romain. 11 Jan 2025. Thales Navigating the EU-US Data Protection Framework. Verified 27 April 2025.

- DORA, DORA. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Dutch National Cyber Security Centre, 16 Aug 2022., How the CLOUD-Act works in data storage in Europe. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission, 10 Jul 2023. EC Adequacy decision for the EU‑US Data Privacy Framework. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. New Standard Contractual Clauses Q&A overview.. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. NIS2 Directive. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/nis2-directive. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. 2 Feb 2016. EU‑US Privacy Shield press release. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. The EU Data Act. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. EU‑U.S. Data Privacy Framework. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. Questions & Answers: EU-US Data Privacy Framework. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. EU Directive 95/46/EC (GDPR). Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Commission. Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Data Protection Board, Guidance on Data Transfers. Verified 27 April 2025.

- European Parliament, Resolution on the adequacy of the EU‑U.S. DPF. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Forrester, Predictions. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Gartner, Data Ecosystem. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Gartner, I-connect007, 7 Nov 2024. Gartner Forecasts IT spending in Europe to grow 8.7% in 2025. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Hava. 2024 Cloud Market Share Analysis: Decoding Industry Leaders and Trends, https://www.hava.io/blog/2024-cloud-market-share-analysis-decoding-industry-leaders-and-trends. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Hengesbaugh, Brian & Feiler, Lukas, 26 Feb 2025, IApp, How could Trump administration actions affect the EU-US Data Privacy Framework?. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Hildén, Jockum, Policy Review. 30 Sep 2021. Mitigating the risk of US surveillance for public sector services in the cloud. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Hunton, Privacy & Information Security Law Blog – Global Privacy and Cybersecurity Law Updates and Analysis, 28 September 2020, U.S. Government Issues White Paper on Data Transfers after Schrems II Decision, verified 27 August 2025.

- Irish Data Protection Commission, Data Protection Commission fines Meta. Verified 27 April 2025.

- GAIA-X,. GAIA‑X Initiative. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Koetzle, Laura, Forester, 22 Oct 2024. Predictions 2025: Europe Will Weather Satellite Interference, Enforce Its AI Regulations, And Invest In Sovereign Cloud. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Kuzmenko, O, Dev.ua. 25 Mar 2025. “The US may not be on the same team with us anymore.” Europe considers ditching American cloud services, including those of Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, amid the Trump administration’s actions. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Microsoft, EU Data Boundary. Verified 27 April 2025.

- Maisto, Dario et al., 15 Apr 2025. Google Cloud Next 2025: Agentic AI Stack, Multimodality, And Sovereignty. Verified 27 April 2025.